SFSMA is delighted to announce the digitization of three full scores for silent films: Ella Cinders (1926) and The Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) compiled and composed by Paul Norman; and La Boheme (1926) by Willian Axt. These are important and fascinating scores that tell us more about musicians’ practices in creating compiled scores and in creating scores for films of opera. We’re grateful to SFSMA supporter and contributor Ben Model for allowing us to digitize these items from his personal collection.

Of these scores, Ben writes, “They were in the collection of Don Lee, whose father Bob Lee ran Essex Films for many years. Essex was a 16mm distributor (dupes of dupes) in the 1960s and maybe 1970s, and sold prints with scores (sometimes on the print, sometimes on cassettes) of scores by Stuart Oderman. Mark Roth of ReelclassicDVD has issued several of these prints with Stuart’s tracks on them on his DVD label. Don gave these two compiled scores to Mark, who sent them to me.”

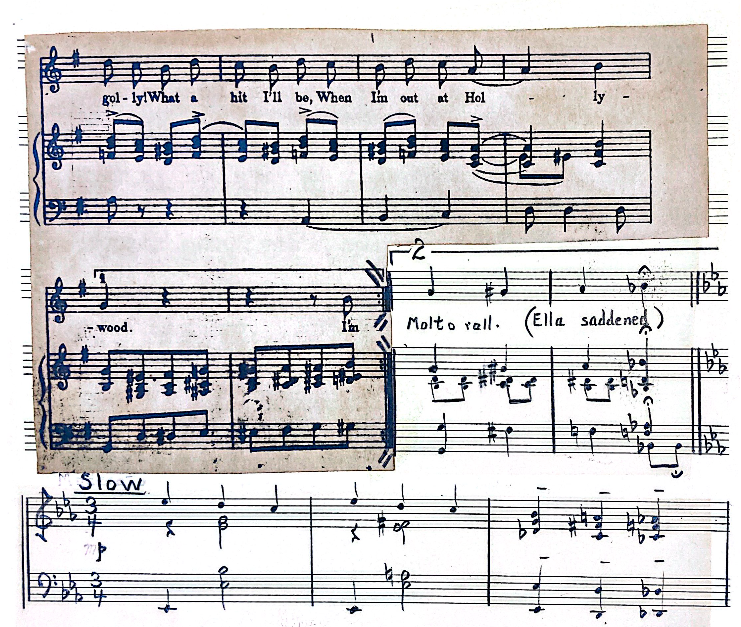

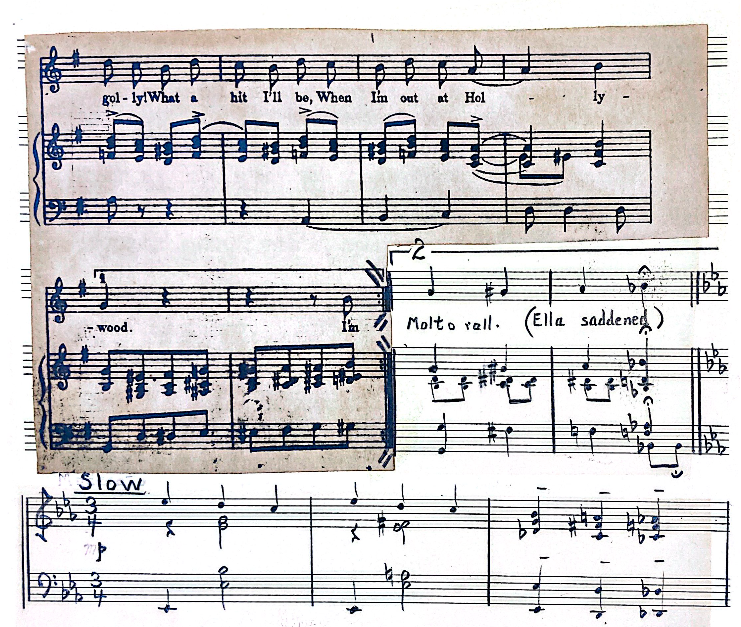

Ella Cinders and The Hunchback of Notre Dame were scored by Norman using a mixture of pre-existing pieces and his own compositions. It’s relatively rare to find a complete compiled score–often such scores, comprised of multiple published pieces by different composers and original material by the compiler–were taken apart so that the music could be used for other films. These two scores also stand out in the inclusion of music composed by Norman for the films. Frequently, cinema musicians would improvise or compose segues between pre-existing pieces when they played a compiled score; in Norman’s scores, there is extensive new music mixed in with the pre-existing pieces, and it is beautifully presented in clear manuscript. In this excerpt from Ella Cinders, you can see how Norman has continued on from a pre-existing piece:

Norman began his career as a cinema pianist and continued to accompany silent films into the 1960s, while also pursuing a career as an organist and composer of mostly sacred music. Norman supposedly gave his library of silent film scores to Arthur Kleiner (Gray), but a search of the Kleiner Collection at the University of Minnesota turns up nothing by or about Norman. If you have any information to add on Norman, we’d love to know. Send us a line at Director@SFSMA.org.

Adaptations of operas for silent film may seem oxymoronic, but they were very popular. The fans of opera singers–like the “Gerryflappers” who adored singer Geraldine Ferrar–encouraged studios to make films starring opera singers or to make films that follow the plot of an opera with popular actors. In La Boheme, which stars Lillian Gish and John Gilbert, the film uses the opera’s plot scene by scene, but uses “original compositions by William Axt, synchronized by David Mendoza and William Axt.” Oddly, though, it includes few tempo markings for the cues and no actual timings for each cue.

These scores should be of interest to researchers working on compiled scores and performers looking for full scores for accompanying these films. If you use these scores–or any other material on SFSMA–let us know! We’d love to feature you in a post.

Works Cited

Gray, Susan. “Kleiner Silent Film Music Collection.” PRX, 2010. beta.prx.org/stories/51949

Further Reading on Compiled Scores and Opera in Silent Film

American Society of Music Arrangers and Composers. “Compiling Silent Film Scores from Historic Photoplay Music with Rodney Sauer.” June 12, 2021. https://www.facebook.com/asmac.org/videos/1099185557279679.

Citron, Marcia J. When Opera Meets Film. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Citron, Marcia J.. Opera on Screen. Yale University Press, 2000.

Fawkes, Richard. “Paul Fryer, the Opera Singer and the Silent Film.” Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 3.2 (2009): 261-266.

Esse, Melina, and Karen Henson. “The Silent Diva: Farrar’s Carmen.” Technology and the Diva: Sopranos, Opera and Media from Romanticism to the Digital Age, ed. Karen Henson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2016), 89-103.

Fawkes, Richard. “The Opera Singer and the Silent Film, and: Carmen on Film: A Cultural History.” Music, Sound, and the Moving Image 3.2 (2009): 261-265.

Grover-Friedlander, Michal. Vocal Apparitions: The Attraction of Cinema to Opera: The Attraction of Cinema to Opera. Princeton University Press, 2005.

Joe, Jeongwon, and Rose Theresa, eds. Between Opera and Cinema. Routledge, 2012.

Leonard, Kendra Preston. “Women’s Compiled Scores in Early Film Music,” in Hidden Harmonies: Women and Music in Popular Entertainment, ed. Paula J. Bishop and Kendra Preston Leonard (University Press of Mississippi, 2023): 53 – 70. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:55389/

Leonard, Kendra Preston. “Using Resources for Silent Film Music.” Fontes Artis Musicae 63.4 (2016): 259-276. https://hcommons.org/deposits/item/hc:14489/

Mosconi, Elena. “Silent Singers. The Legacy of Opera and Female Stars in Early Italian Cinema.” (2013): 334-352.

Sauer, Rodney. “Photoplay Music: a Reusable Repertory for Silent Film Scoring, 1914-1929.” Americas: A Hemispheric Music Journal 8 (1998): 55.

Schroeder, David. Cinema’s Illusions, Opera’s Allure: the Operatic Impulse in Film. Bloomsbury Publishing, 2016.

Whitmer, Mariana. “Silent Westerns: Hugo Riesenfeld’s Compiled Score for The Covered Wagon (1923).” American Music 36, No. 1, (Spring 2018), 70-101.

Wolf, Stephanie. “Q & A: Mont Alto Orchestra’s Rodney Sauer on Scoring Silent Films.” CPR News, Oct. 30, 2014. https://www.cpr.org/2014/10/30/q-a-mont-alto-orchestras-rodney-sauer-on-scoring-silent-films/